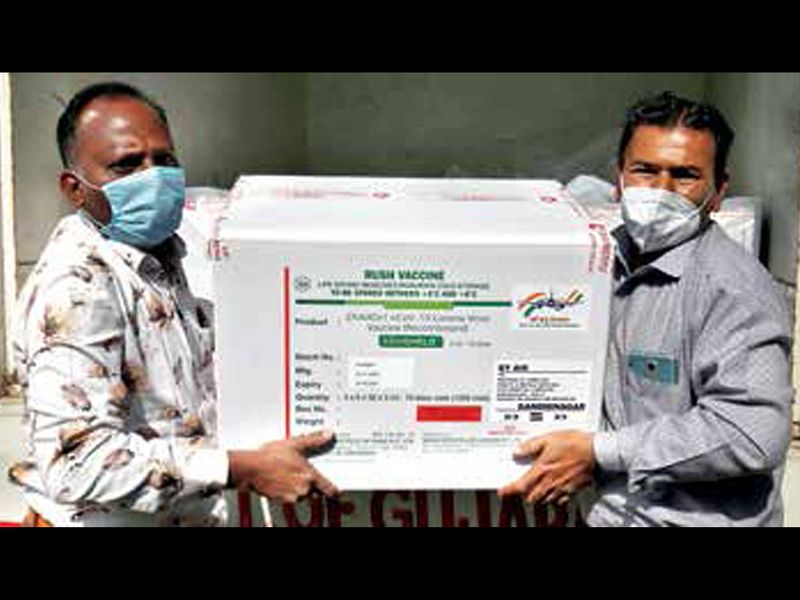

On January 16, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi flagged off the world’s biggest inoculation drive. The mammoth exercise, which will extend into 2022, involves delivering Covid-19 vaccines to 1.38 billion Indians. It also requires that those vaccinated turn up again a month later for their second booster dose. It is an unprecedented logistical exercise, challenged by India’s size and an uneven spread of cold storage facilities.

But India has been in similar, albeit less complicated, situation before, specifically with its polio immunisation activities.

Lessons from polio eradication

Ashok Mahajan, who heads the Covid task force of Rotary International’s India National PolioPlus Committee (INPPC), observes that India was one of the most difficult locations in the world for polio eradication, given its vast population, diverse terrain and varied climate patterns. “We expect many of the same challenges as our population is immunised against Covid-19. The mission is achievable, especially if we look to the polio eradication programme as a roadmap,” he says.

India can leverage the infrastructure and expertise that the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners have established in the country, which is currently being used to store, transport, and disseminate other critical vaccines. The government can also count on corporations and NGOs pitching in.

“Spread across nearly 4,000 clubs in India, over 150,000 Rotary members are already taking action in their communities. As other organisations and entities get involved, I am confident that together, we can stop the coronavirus in India,” asserts Mahajan.

Supply chain burden

Dr K Hari Prasad, President of Apollo Group of Hospitals, states that vaccinating India is technically equivalent to vaccinating the entire continent of Africa.

“While procurement, logistics and workforce remain the challenge, I am positive the phased approach of targeting priority segments to start with is the ideal way forward here,” he says, adding that the enabling factor comes with technology and possible involvement of private segment.

Currently, India’s vaccine distribution network is primarily operated through four government medical store depots in Karnal, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. About 53 state vaccine stores get their supplies either from these facilities or directly from manufacturers. The country has around 28,000 cold chain points and 85,000 cold chain equipment.

“We do not foresee a major challenge in terms of air freight capacity to meet the vaccine supply chain demand. In fact, storage at ports and the logistics infrastructure to handle in-transit movement, are available and capable of handling the load surge,” says Vickram Srivastava, an expert in logistics for the pharma sector and Head of Planning – Supply Chain Management at Ipca Laboratories. He, however, adds that the real challenge will be the last mile connectivity to far-flung locations, while ensuring cold chain integrity of the vaccine before it is finally administered to the patient. Secondly, availability of trained medical professionals to administer vaccines at such a large scale has never been done in the history of mankind and could prove to be challenging.

“This is a chance for India to showcase its readiness on connected products, connected operations, and connected data,” says Anirban Bhattacharyya, a supply chain expert and Board Member of the AI-driven platform, Amplo Global. He asserts India must leverage the air travel industry, which is suffering from low sales, to land shipments in places where flight frequencies are low. Also, creating real time dashboards and predicting via data analytics will be of immense help to healthcare workers.

Technology at the forefront

The government has taken steps towards digitisation of the vaccination drive by launching the Covid Vaccine Intelligence Network (Co-WIN). The platform can track the use and availability of Covid vaccines across the country, even at sub-district levels, and it has been integrated with the world’s largest demographic database, Aadhar. The system is based on India’s existing real-time supply chain management system known as the electronic vaccine intelligence network (eVIN), which as of August 2020, was enabled in 32 states and union territories.

the smooth and multi-phase conduct of the world’s largest democratic exercise — Indian general election — has given the country the institutional know-how to easily run large-scale exercises.

Dr Harish Pillai, CEO – Aster India, Aster DM Healthcare, insists that the “beauty of India” is the multi-decade experience in managing one of the world’s largest universal immunisation programme – Pulse Polio.

“Moreover, the smooth and multi-phase conduct of the world’s largest democratic exercise — Indian general election — has given the country the institutional know-how to easily run large-scale exercises.”

Dr Pillai states that the administration of the Covid-19 vaccines is being monitored by the prime minister himself, and review conferences have been held with all state chief ministers and the district officials. To test the infrastructure and iron out issues, practice dry runs have been conducted in several rounds across 736 districts and 33 states and union territories, with both public and private hospitals. This includes cold chain logistics network, training of human resources, beneficiary verification and the management of any potential adverse events.

And unlike the Pfizer vaccine, which requires -70 degrees centigrade for storage, the two Made in India vaccines, Covishield and Covaxin, are easier to store and transport, requiring temperatures of just 2 to 8 degrees centigrade. Dr Pillai points out that this is a major advantage since the vaccines can be stored using the existing cold chain system.

“Overall, the country remains confident in the smooth administration of the Covid-19 vaccination across 1.3 billion of its citizens.” ●

from World,Europe,Asia,India,Pakistan,Philipines,Oceania,Americas,Africa Feed https://ift.tt/3otNs38

No comments:

Post a Comment