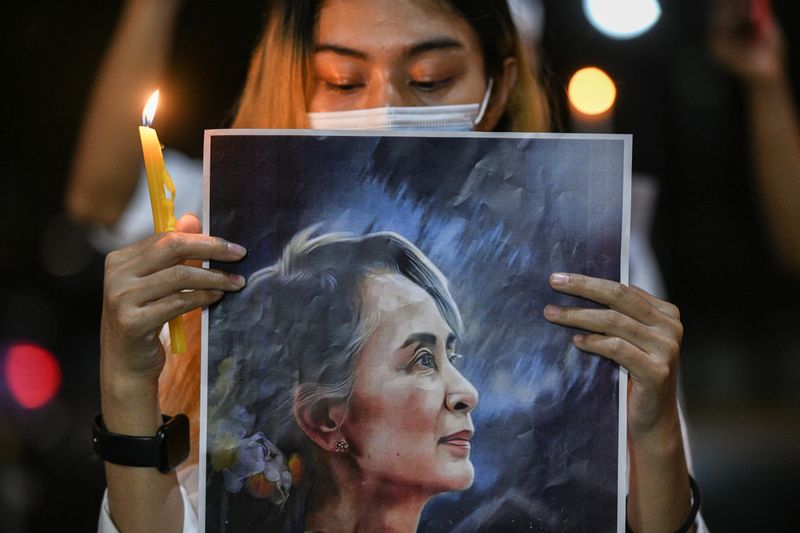

Dubai: In Myanmar, tens of thousands of people protested on Sunday against last week's coup and demanded the release of elected politician Aung San Suu Kyi, who created for herself the role of ‘State Counsellor’, which in essence made her the leader of the country. The protests are being seen as the largest people’s movement since the so-called ‘Saffron Revolution’ in 2007 which led to democratic reforms that bought Suu Kyi to power.

In Yangon, crowds sported red shirts, red flags and red balloons, the colour of Suu Kyis National League for Democracy Party (NLD). We dont want military dictatorship! We want democracy! they chanted, according to Reuters. The internet was restored in the country by the military, as its shutdown had become another lightning rod for the protesters.

Why carry out a coup when you are already in power?

Myanmar’s coup has been described as a “pre-emptive strike”. The military, known as the Tatmadaw, invoked the Constitution (which it drafted in 2008, giving it the right to keep 25% of the seats in parliament) to declare a state of emergency for a year.

According to the New York Times, the Tatmadaw has manufactured a crisis so that it could step in again as the purported saviour of the Constitution and the country, while vanquishing an ever-popular political foe. There is also the question of poor relations between Suu Kyi and General Min Aung Hlaing. The two have rarely met since 2015. Both are Buddhists, and ethno-nationalists from the same ethnic Bamar majority. And both believe they have the right to rule.

Myanmar’s military controls is in charge of a vast business empire - with interests in mining, telecommunications, textiles, and hotels. But analysts believe the military is not primarily motivated by financial concerns. Richard Horsey, a Myanmar-based analyst, told the Washington Post: “They never really have been. This is about pride, politics and personal ambition. More broadly, they have felt for some time that the civilian government was not giving them and their concerns due weight and respect, and was not following the constitutional rules.”

That includes Suu Kyi’s decision to circumvent a constitutional law barring her from the presidency by creating a higher position for herself in 2016, that of “state counselor.” And it likely included her refusal to entertain the military’s charges of election fraud by convening a special session of parliament over the matter.

“This seems to be the only way to explain the military’s actions, which are so fundamentally against its own interests and the interests of the country,” Horsey said.

Who is Gen. Min Aung Hlaing?

Myanmar’s new military ruler, senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, 63, was being forced into retirement in 2016 as head of the Tatmadaw. But, he wrestled his way thorough, and extended his term by five years, due to end in a year. Due to this, there has been speculation that the coup was designed to preserve the general’s position.

According to the Washington Post, Min Aung Hlaing also holds top positions at Myanmar Economic Holdings and Myanmar Economic Corp., the secretive military-owned duopoly that has cornered the most lucrative parts of the economy. The two conglomerates have been challenged to some degree by demands for more transparency and calls by the United Nations and Amnesty International for a boycott because of the Tatmadaw’s dismal human rights record.

The US has already imposed sanctions on Min Aung Hlaing in 2019 for his role in the brutal crackdown on the Rohingya Muslim minority, hundreds of thousands of whom have been displaced and terrorised in military sweeps.

Suu Kyi: From Nobel prize to international outcast

Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her fight against the military junta. The Norwegian Nobel Committee dubbed it “one of the most extraordinary examples of civil courage in Asia in recent decades.”

As a result of this, she enjoyed stupendous support in the international liberal community, with the global media, activists, and leading Western politicians batting for her. But now, her reputation lies in tatters after serious and well-founded allegations that as Myanmar’s leader she turned a blind eye to ethnic cleansing and genocide of the Rohingya Muslim minority.

It was Suu Kyi’s defence of Myanmar’s military during a campaign that saw more than a million Rohingya driven from their homes in 2017 that changed the perception of her. UN investigators later said Myanmar’s military operation against the Rohingya had “genocidal intent.”

Suu Kyi did not just seem to condone the military actions: She publicly defended them. In 2019, she became the first head of state to answer questions at the International Court of Justice, where she refused to even say the word “Rohingya,” repeating military claims of terrorist interlopers.

The actions against the Rohingya led many people to drop their support for Suu Kyi. Her former biographer said she should resign. “What happened to Aung San Suu Kyi?” former Obama foreign policy official Ben Rhodes wrote in an essay for The Atlantic in 2019.

The international outrage did little to dent her domestic appeal, however, and her party won 396 of 476 seats in Myanmar’s parliament in November. Her popularity appears to have caused the military to arrest her and accuse her party of electoral fraud.

Why do Rohingya think coup will worsen their plight?

The developments are also being watched with particular alarm across the border in Bangladesh, where more than one million Rohingya Muslims have sought refuge since 2017 after fleeing a military-led crackdown on their communities in Myanmar.

Among the Rohingya, there is trepidation that a Myanmar led by the military would be worse than the ousted civilian-led government, Tun Khin, president of the Burmese Rohingya Organisation United Kingdom, told The Washington Post.

“This military is very brutal, and Rohingya worry that the military may commit more violence against Rohingya,” Khin said. “We worry more may flee.”

Kaamil Ahmed, a journalist previously based in Bangladesh who is writing a history of Rohingya refugees, told the Post that the United States and others in the international community had initially sought to tread softly around majority-Buddhist Myanmar’s treatment of the majority-Muslim Rohingya to protect what they hoped would be the country’s democratic transition.

That calculus, he said, could change in the wake of the coup.

“If that facade (of a democratic transition) has been destroyed, then there’s a question about whether the international community, and especially the new Biden administration, is going to be more forthright,” Ahmed said. “The Rohingya are begging for a more serious international intervention, one that actually acknowledges what is happening,” he continued. “It hasn’t come, it seems, because they have seemed so invested in a democratic transition in Myanmar. And now the question is: Is that going to change?”

How are the youth reacting?

There is shock and anger among the youth in the country, given that the coup was an unexpected blow. Opposition to the junta is growing, but there are fears that mass demonstrations could lead to a brutal massacre as in the past.

The youth are demanding Suu Kyi’s release, and that of President Win Myint, leaders of the ousted National League for Democracy ruling party, who remain under house arrest on dubious charges.

The Los Angeles Times reported, meanwhile, that acts of civil disobedience are gaining steam, despite authorities having blocked access to Facebook — a primary mode of communication — to try to blunt any organised opposition.

On Friday, hundreds of students at Dagon University in Yangon, Myanmar’s most populous city, marched on campus in opposition to the coup. They flashed the three-fingered salute that has become synonymous with the democracy movement in neighboring Thailand and that was inspired by the “Hunger Games” films. At Yangon University of Education, scores of teachers chanted, “Long live Mother Suu,” a reference to Suu Kyi, while holding signs with the red-ribbon symbol of resistance.

In Mandalay, a group of around 20 protesters gathered outside the Mandalay Medical University on Thursday, displaying banners condemning the military and demanding the release of detained civilian leaders. At least three activists were arrested.

Civil servants from various ministries, along with doctors, student unions, teachers and employees of military-linked companies, have launched strikes and work stoppages. Others are calling for boycotts of military-owned businesses, ranging from insurance companies to beer and rice products.

What does the future hold?

Having tasted relative freedom for the past decade or so, the people of Myanmar are very unlikely to take the coup lying down. They do not want to go back to the past, where the military ruled directly. There is still hopes that through talks, the impasse can end and the situation be resolved. However, if the protests gather steam, there is a high chance of a full-blown crackdown. If that happens, a major crisis group grip the country.

-With inputs from New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times

from World,Europe,Asia,India,Pakistan,Philipines,Oceania,Americas,Africa Feed https://ift.tt/3pXi5PX

No comments:

Post a Comment