Dubai: Detained Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi appeared in court via video hearing on Monday and additional charges were levelled against her, adding two more years to any sentence she might receive.

Supporters marched in several towns and cities in defiance of a crackdown after security forces killed at least 18 people in protests on Sunday.

Suu Kyi, aged 75, looked in good health during her appearance before a court in the capital Naypyidaw, one of her lawyers said.

Read more

Here’s a look at what triggered the crisis in Myanmar and the reaction so far.

What is the problem in Myanmar?

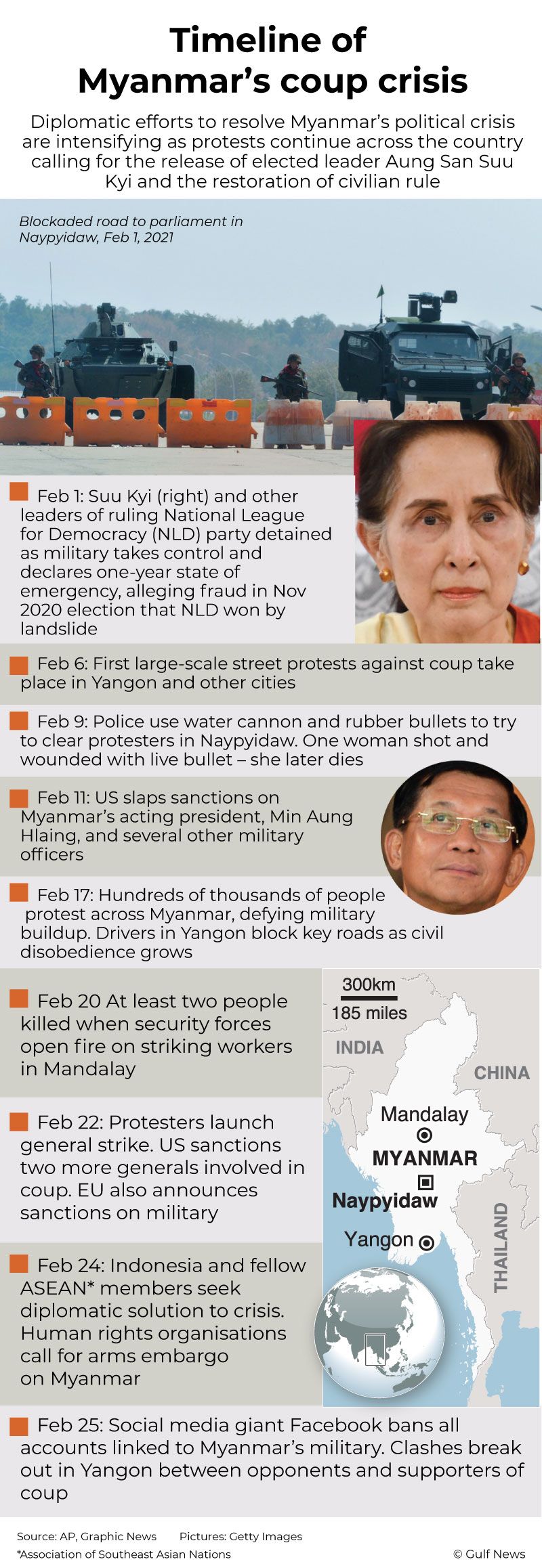

Myanmar’s generals staged a coup on February 1 following which Nobel peace laureate Suu Kyi and her top political allies were detained. The move ended Myanmar’s decade-long experiment with democracy after close to half a century of military rule.

What was the trigger?

In the Myanmar elections held in November, Suu Kyi's party captured 396 out of 476 seats in the combined lower and upper houses of Parliament. The state Union Election Commission confirmed that result.

But the generals claim that there was fraud, including millions of irregularities in voter lists in 314 townships that could have let voters cast multiple ballots or commit other "voting malpractice."

The election commission has rejected the claims, stating there was no evidence to support them.

The military takeover came on what was scheduled to be the first day of the new Parliament following the elections.

What are the charges against Suu Kyi?

Suu Kyi is among more than 1,000 people detained since the Feb. 1 coup. She was initially charged with illegally importing six walkie-talkie radios. Later, a charge of violating a natural disaster law by breaching coronavirus protocols was added. The charges carry likely terms of six years in prison.

On Monday she was additionally charged with incitement under section 505(b) of the country's penal code used by the authorities to criminalise speech "likely to cause fear or alarm in the public," her lawyer Khin Maung Zaw said.

Another charge was added under the telecommunications law for owning equipment without the necessary licenses, Myanmar Now reported, citing lawyer Min Min Soe. That charge could add a year to the ousted leader's likely punishment, Reuters reported.

How have the people responded?

Resistance to the coup began with people banging pots and pans - a practice traditionally associated with driving out evil spirits.

Dissent surged over the days with tens of thousands of people gathering on the streets calling for the release of Suu Kyi.

Workers began a nationwide strike on February 8.

How did the military react?

The military leadership tried to block social media platforms including Facebook, which is hugely popular in the country. Later, internet blackouts at night were imposed. The military warned of a crackdown and imposed night-time curfews including in Yangon, Mandalay and Naypyidaw - the country's three biggest cities.

On February 9, a young woman was shot in the head and another wounded after police fired on crowds in Naypyidaw.

Over the next few days, two more protesters were killed in police firing.

But in an escalation on Sunday, troops and police fired live bullets on unarmed demonstrators across the country. The UN says it has credible information at least 18 people had died.

What is the international response?

The coup has drawn global condemnation, from Pope Francis to US President Joe Biden.

The US has announced sanctions against several military officials, including General Min Aung Hlaing, the army chief now in charge.

Britain sanctioned three Myanmar generals on February 18 for post-coup rights violations, and Canada has taken similar measures.

The UN chief Antonio Guterres has rebuked the junta's "brutal force", with the European Union later agreeing to sanction the military. The G7 group of the world's wealthiest nations have condemned the military coup.

What is Facebook’s role in Myanmar?

For decades Myanmar was one of the least-connected countries in the world, with less than 5% of the population using the internet in 2012, according to the International Telecommunication Union. When telecommunications began to be deregulated by a quasi-civilian government in 2013, the price of SIM cards for cellphones plummeted, opening a new market of users, AP reports.

Facebook was quick to capitalise on the changes, and soon began to be used by government agencies and shopkeepers alike to communicate.

Myanmar had more than 22.3 million Facebook users in January 2020, more than 40% of its population, according to social media management platform NapoleonCat. For many in the country, Facebook effectively is the internet.

What criticism has Facebook faced in Myanmar?

The social media platform has faced accusations of not doing enough to quell hate speech in the country.

In a 2018 report on army-led violence which forced more than 700,000 ethnic Rohingya Muslims to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh, Marzuki Darusman, head of the UN Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, said Facebook “substantively contributed to the level of acrimony and dissension and conflict.” He added, “Hate speech is certainly of course a part of that,” AP reported.

Under pressure from the UN and international human rights groups, Facebook banned about 20 Myanmar military-linked individuals and organisations in 2018, including Commander in Chief Min Aung Hlaing, for involvement in severe human rights violations.

Why is Facebook banning more pages now?

After the coup, Facebook said it would reduce distribution of all content from Myanmar's military, called the Tatmadaw, on its site, while also removing content that violates its community standards, including hate speech.

Facebook has announced that it will ban all remaining Myanmar military-related entities from Facebook and Instagram, as well as ads from military-linked businesses.

“Events since the February 1 coup, including deadly violence, have precipitated a need for this ban. We believe the risks of allowing the Tatmadaw on Facebook and Instagram are too great,” the company said a statement.

The ban covers the air force, the navy, the Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Border Affairs, Facebook Policy Communications Manager Amy Sawitta Lefevre said.

Facebook said it will leave up pages contributing to public welfare, including those of the Ministry of Health and Sports and the Ministry of Education.

Does this make a difference?

The decision deprives the military of its largest communication platform. Facebook said it expects the military will attempt to regain a presence on the platform.

- with inputs from Reuters, Bloomberg and AP

from World,Europe,Asia,India,Pakistan,Philipines,Oceania,Americas,Africa Feed https://ift.tt/3dTUgpc

No comments:

Post a Comment