Kolkata: India is suffering from a spike in COVID-19 infections, with a daily surge in cases. Gulf News takes a closer look at the ‘whys’, ‘hows’ and ‘whats’ of a profound humanitarian crisis that is currently unfolding in the second-most populous nation in the world.

How bad is the current situation in India?

Just consider the following set of statistics:

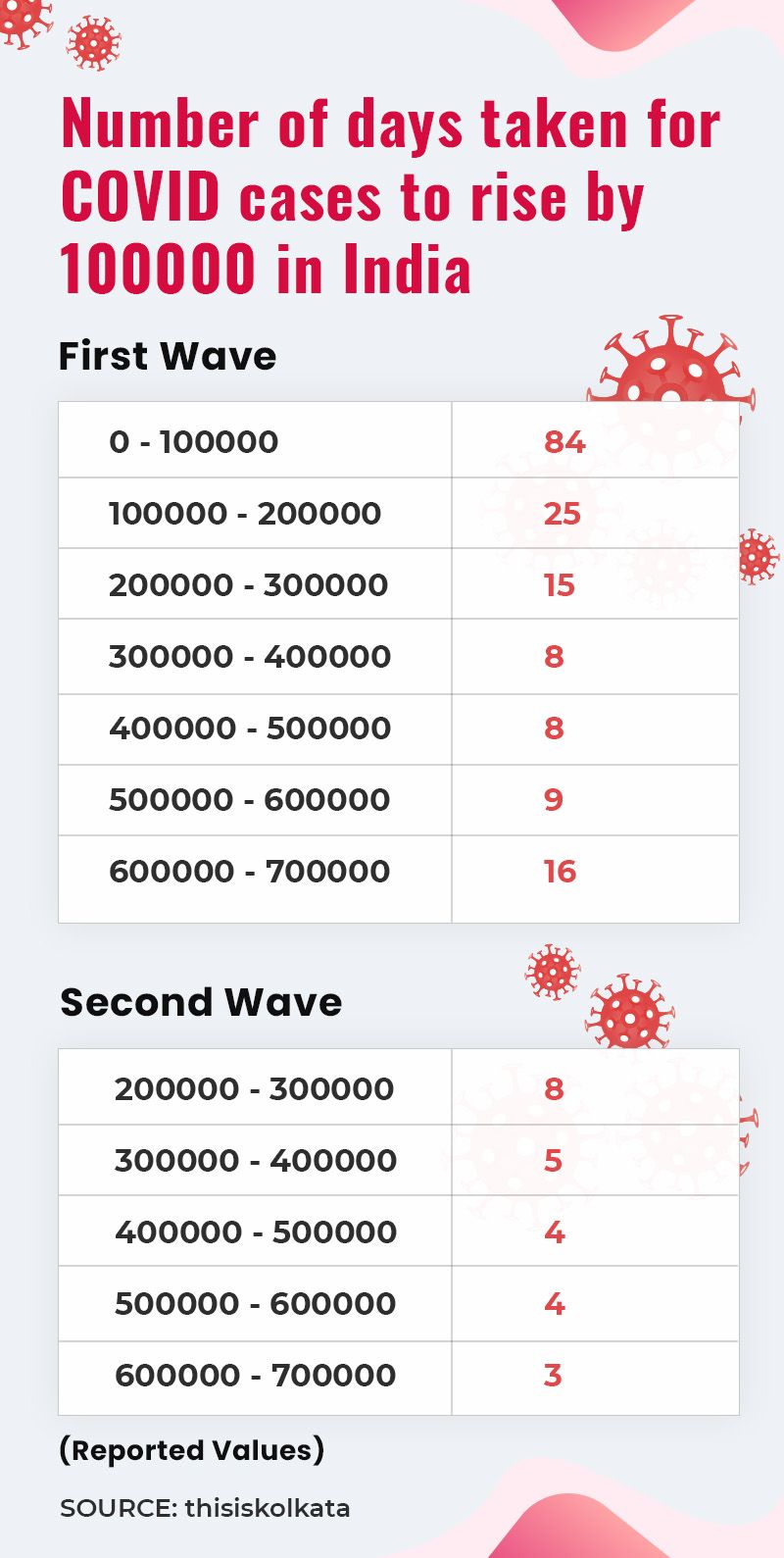

During the ‘first wave’, it took 15 days for the number of positive cases in India to go up from 200,000 to 300,000. In the ‘second wave’, the same figures were reached in just eight days. And, while it took 16 days for the number of positive cases to rise from 600,000 to 700,000 during the ‘first wave’, in case of the ‘second wave’, the same numbers have been reached in only three days! You read it right – three days! India’s active case-load stood at 16,960,172 on Sunday, with 192,311 deaths so far and 14,085,110 recoveries.

According to an independent estimate on Sunday afternoon, in Kolkata, every second person who was being tested for coronavirus was returning a positive result. For a city with a population of 14.9 million and with a population density of 22,000 per square kilometre, these are scary numbers by any assessment.

And the picture isn’t any less scary in the rest of the country. Maharashtra has been consistently recording daily positive cases in excess of 60,000 for the last several days. On April 21, Delhi recorded its highest daily spike of 28,395 positive cases. Every third person who underwent the test in Delhi returned a positive result. In the south of India, the picture is equally grim. In Karnataka, Bengaluru district, which now has the highest active case burden in the country, reported an all-time single-day high of 17,342 coronavirus cases and 149 deaths last Saturday.

How and why did India fail to read the ‘second wave’?

India did reasonably well in managing the ‘first wave’. From declaring a nationwide hard lockdown in less than two weeks after WHO declared it a pandemic in March 2020 to optimising its health-care infrastructure and frontline workers, a nation of 1.3 billion took the challenge in all its seriousness and the fact that India’s death toll and infection rate were both lower than many advanced countries in the world, including the US and Britain, bear testimony to a country rising up to the challenge.

But unfortunately, that was just about it. As the infection rate and death toll started plummeting significantly by the end of 2020, India threw caution to the wind and went about its daily life as if coronavirus never stalked planet Earth. From concerts to weekend picnics to political rallies and roadshows, India’s COVID-19 protocol and safety precautions went out of the window.

Reacting to a query on why and how India underestimated the ‘second wave’, Dr Deepak Das Roy, paediatrician at Calcutta Medical College and Hospital, told Gulf News on Sunday: “This is a man-made disaster. We have just allowed this crisis to come upon us. The frontline warriors did their best and managed to restrict the damages from the ‘first wave’ around June-July last year. A hard lockdown also helped a lot in creating a buffer. But thereafter, we just let our guard down. In West Bengal, for instance, the entire COVID-19 response unit in the health-care sector was dismantled as the number of positive cases started declining around the end of last year. The election in West Bengal and four other states saw political parties indulge in massive rallies and roadshows, throwing every protocol out of the window and giving people the false impression that ‘there is no Corona’! The results are now here for everyone to see.”

What is the ‘triple mutant’ strain?

The ‘triple mutant variant’ or the ‘Bengal strain’ is a new variant of coronavirus that is currently sweeping through India. This variant is being technically referred to as ‘B.1.618’. It is the second lineage of the SARS-CoV-2 virus detected in India. This particular variant is the most infectious of all the variants of the virus detected since late 2019. While this particular variant has been predominantly active in the state of West Bengal, its traces have already been noticed in Delhi and Maharashtra. Traces of the same variant have also been found beyond India – in Switzerland, United States, Finland and Singapore. Epidemiologist Dr Kajal Krishna Banik told Gulf News in Kolkata: “Apart from the known mutants there may be some which are more potent. It depends on the change in the genomic sequences of the virus. It is said that the original UK strain already had its mutations at two positions. But overall, this ‘second wave’ is resulting in lesser mortality – relatively speaking. Viruses that cause a higher mortality rate have a lesser chance to propagate and propagation is must for this compulsory endoparasite SARS-CoV-2.”

Why is the current strain so virulent?

Virologists are yet to ascertain the efficacy of all the available vaccines against this ‘triple mutant variant’. However, what is a real cause for concern right now is the presence of E484K mutation in this ‘triple mutant variant’. E484K is believed to be a major immune-escape variant and that is why the ability of any of the available vaccines until now to fight this particular variant may be very limited or nil. This is primarily owing to the fact that whatever antibodies are generated in the system due to vaccination, which in turn are supposed to boost the body’s immune system to fight the virus, will not be effective in battling this ‘triple mutant variant’ because of its immune-escape capabilities.

The second cause for concern with this ‘triple mutant variant’ is that in some cases reported in and around Kolkata over the past few weeks, the virus had directly affected the lungs of the infected patients. In some patients who contracted this latest strain, the RT-PCR tests had thrown up negative results because there were no traces of the virus in their nasal or throat swab. However, as the patients’ conditions deteriorated very fast, an X-ray of the lungs revealed massive white patches, indicating fluid formation and confirming unmistakeable traces of the virus.

However, there is another school of thought that says that the ‘double’ and ‘triple’ mutants are the same. Basically, they are both identified by the technical name ‘B.1.617’ and that there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that the ‘triple’ variant is more virulent. According to this theory, the existing vaccines are effective enough to develop immunities against the new variant. Dr Soumitra Das, director, National Institute of Biomedical Genomics, speaking at a webinar on ‘Genome Sequencing of SARS-CoV-19’ on Friday said that the ‘double’ and ‘triple’ mutant variants are “overlapping terms” that are primarily “colloquial” as both refer to B.1.617. He further said: “Variants found in India are not really escaping our vaccinated sera.”

As the virus keeps mutating, is this the worst phase or is the worst still to come?

Replying to this query, epidemiologist Dr Kajal Krishna Banik told Gulf News: “Usually mutations lead to greater infectivity because the mutated strains of the virus can overcome or try to overcome any kind of ‘herd immunity’ (immunity achieved by persons infected in the ‘first wave’) that may have set in or is likely to set in. Now, it is quite possible that the virus may become less virulent as it keeps mutating, but the problem is that as the infectivity is still very high, a large number of people keep contracting the virus and so there is every possibility of the overall death toll increasing. Keeping this scenario in mind, many experts feel that the peak for the current ‘wave’ will probably be reached around May end-mid June.

Usually mutations lead to greater infectivity because the mutated strains of the virus can overcome or try to overcome any kind of ‘herd immunity’ (immunity achieved by persons infected in the ‘first wave’) that may have set in or is likely to set in...

Dr Das Roy agreed with Dr Banik, saying: “What we are seeing right now in India isn’t even the peak. The peak will probably be reached by May-end or mid-June when the numbers will be even more scary.” However, he had one crucial silver lining to offer. According to Dr Das Roy, since the number of positive cases has seen such a sharp rise, it is quite possible that by end June or middle of July, the number of new infections may see a sharp fall too. “Since the rise has been so sharp, the active case-load can also come down sharply because what we are seeing right now, in spite of all the scary statistics, could also be the harbinger of a ‘herd immunity’ setting in,” he said.

Why have the numbers of relatively young people contracting the virus gone up this time?

According to epidemiologist Dr Banik, since the ‘second wave’ of the virus has a much higher infection rate than the ‘first wave’, the “innate immunity” that the younger age-group had, which stood them in good stead in fighting the infection during the ‘first wave’, is now no longer effective. In addition to that, a sense of complacency is also responsible for younger people falling victim to the virus this time around. “Innate immunity played a very crucial role in protecting the younger age-group in the ‘first wave’. As a result, though many young people contracted the virus in the ‘first wave’, they were able to come out of it without much of a damage. But this gave rise to a certain sense of complacency among the youth. Many thought that they had ‘beaten Corona’ and let their guard down by the time the ‘second wave’ struck.”

How effective can a lockdown be at this point?

Many epidemiologists believe that a lockdown as such cannot be considered as the sole method of control. “A lockdown should be aimed at imposing certain restrictions on movements and gatherings. During that period, necessary reinforcements must be shored up, particularly in the health-care sector. But a lockdown cannot be seen as a remedy as such,” Dr Banik explained. In fact, Dr Randeep Guleria, director, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, went a step ahead and suggested, during his interaction with a television channel in New Delhi recently, that a lockdown can be imposed in areas where the infection rate is above 10 per cent. Ruling out a complete nationwide lockdown at this stage, Dr Guleria said that smaller containment zones can be created where the infection rate is high. “That can help bring down the number of new infections and that is very important because all these areas where the rate of infection is high are creating a massive pressure on the health-care system in the rest of the country. So containment zones can be built and there can be a lockdown in those areas only,” Dr Guleria explained.

Case study:

When 51-year-old self-employed academic Sumit Bhattacharjee complained of fever and body ache last week, his wife Suparna, who is senior manager, patient services, at Advanced Medical Research Institute in southern Kolkata, was sceptical. Soon, an RT-PCR test was conducted and the result was positive.

“For the first three days after testing positive for COVID-19, my husband had fever and body ache, but his oxygen saturation was still normal. However, when his fever shot up, I decided to get him hospitalised. My first worry then was securing a hospital bed for him. Fortunately, because I’m myself an employee in the health-care sector, I managed to get a bed without much difficulty. But I’m sorry to see how so many others are struggling to get their near ones admitted. The hospital that I work for has a bed management system that has by and large worked well under these stressful circumstances. It is called ‘bed augmenting’, whereby, we prioritise bed allotment depending upon our own assessment of the condition of an incoming patient and also those who are already under treatment at the hospital. At least that way we can maintain some modicum of a fair distribution. However, this is not necessarily the case at other health-care facilities,” Suparna said.

Speaking to Gulf News over the phone from his hospital bed on Sunday evening, Sumit said: “Proper care and medication right from the first couple of days after I contracted the virus made all the difference. My temperature has subsided and I’m by and large symptom-free right now. However, my system struggled getting used to Remdesivir [the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States for treating COVID-19 patients]. I kept throwing up practically whatever I ate or drank for the last two days. So the doctors had to stop Remdesivir today and I’m way better now. In addition, my pulse rate had shot up a lot as my temperature touched 103 [degrees Fahrenheit]. But I’m feeling a lot better now though there is severe weakness even now.”

“Looking at my husband’s condition, I can say for sure that there are a few lessons I have learnt about this dreaded virus. Firstly, one should never take it lightly. Ensuring that a patient has access to the right medicines and following the right treatment protocol are absolutely essential. Along with that, proper diet is also very crucial because this virus can leave one physically ravaged. But perhaps even more important than all these is being open and transparent about the truth. My husband, just before he contracted the virus, had visited a household where several members were already down with fever, but that information was withheld from him. We must always remember that being honest with our condition can actually help save many others from contracting COVID-19,” Suparna added.

Quick takes:

Positivity rate: This is an indicator of the spread of the virus in a certain community. According to WHO, a 5 per cent positivity rate is considered to be the threshold for the COVID-19 pandemic to be seen as under control. From 1.47 per cent on February 13, 2021, India’s positivity rate went up to 10.7 per cent on April 11, 2021.

Spread of the virus: Currently, five states in India account for 67 per cent of total active cases. These five states are Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka.

Days taken for cases to rise: In the ‘first wave’, the number of positive cases reached from 600,000 to 700,000 in 16 days. In the ‘second wave’, the numbers jumped from 600,000 to 700,000 in just three days.

from World,Europe,Asia,India,Pakistan,Philipines,Oceania,Americas,Africa Feed https://ift.tt/3tVEBL4

No comments:

Post a Comment